When ACT announced Superscore reporting and Section Retesting in the fall of 2019, it had no way of knowing that a 2020 rollout would be upended by a pandemic. Superscore reporting finally became available this month (April 2021), whereas Section Retesting is still on hold. Compass covers how students can evaluate and order the Superscore report and what information colleges actually receive and use.

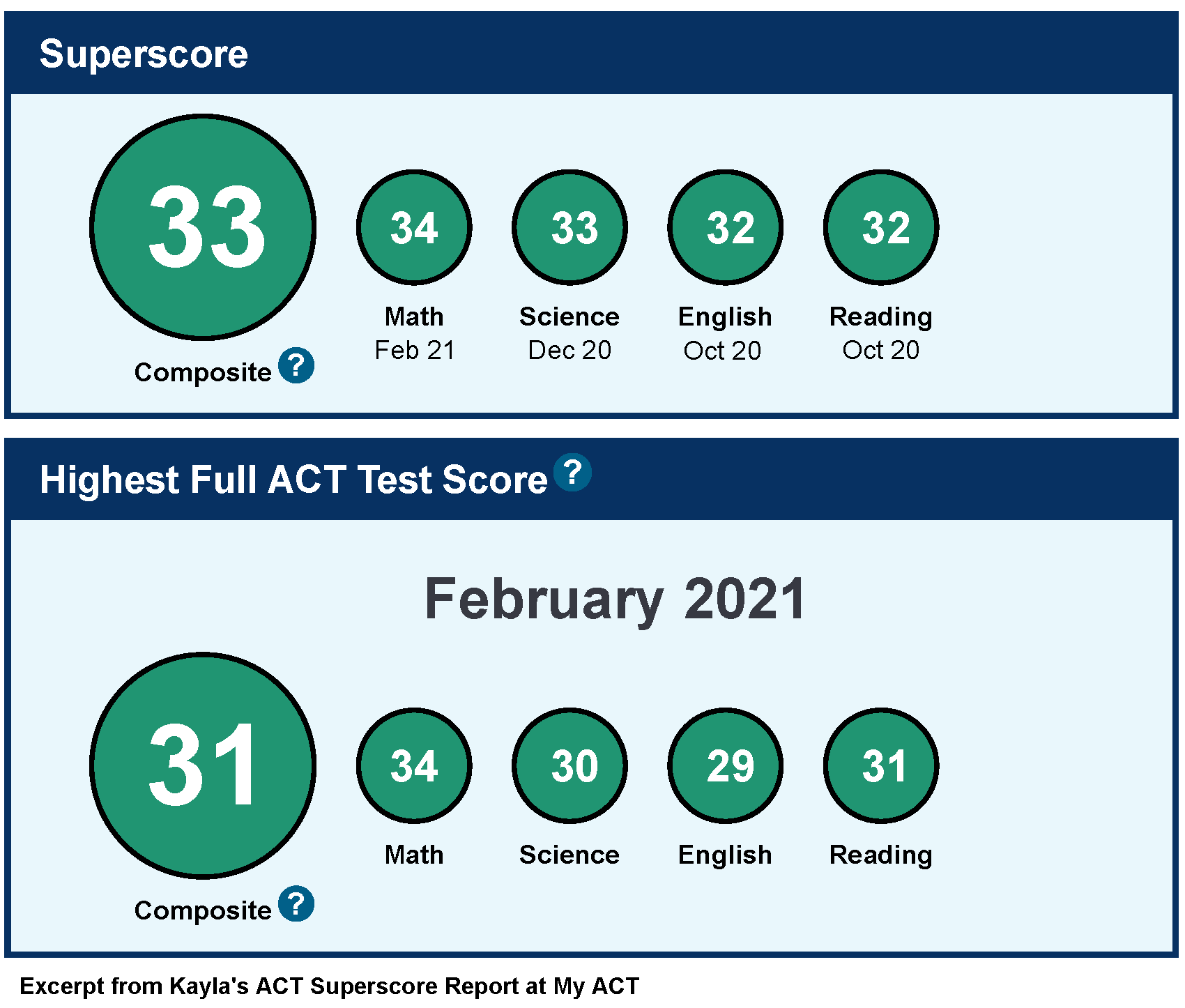

ACT is heavily promoting the new reporting option. Students with more than a single test will be greeted with superscores whenever they log in to my.act.org, and a banner lives at the top of almost every page. ACT’s enthusiasm, though, has not yet translated into more colleges announcing superscoring. You can find the current policies of hundreds of schools at Compass’s Superscoring and Score Choice page.

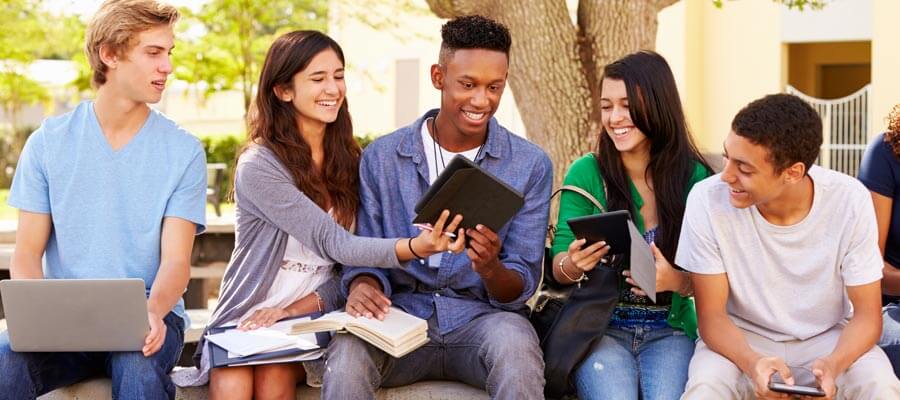

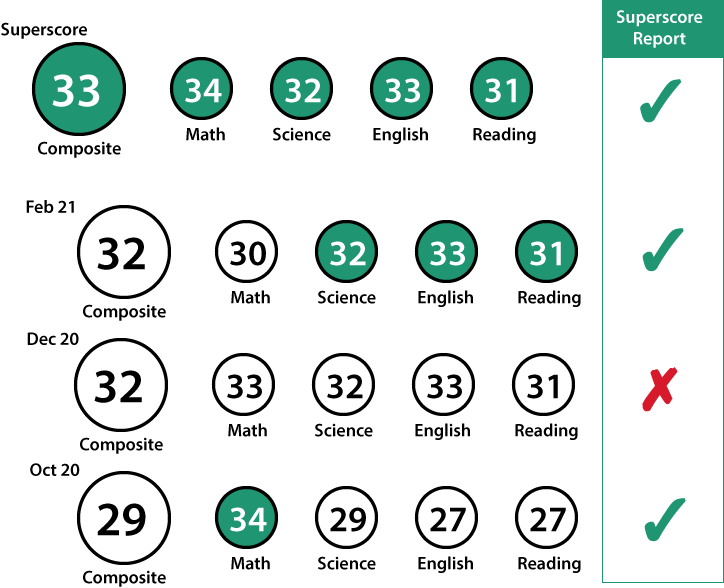

When students provide two or more ACT scores, colleges need to decide how to treat those scores. In some cases, a college’s policy is only to look at the test date with the highest Composite score, even when a superscore is included in the report. In the case of sample student Kayla Brooks, those colleges would look at her February 2021 Composite of 31.

The trend, however, has been for colleges to view scores supportively and to evaluate students’ best efforts in each subject area. Kayla got her best Math score in February, but her other high scores came from tests she took earlier in October and December. A superscore combines her top performances and provides a new and improved Composite score. Colleges that superscore — about two-thirds of selective institutions — would consider Kayla’s ACT Composite to be 33.

Prior to ACT’s Superscore report, Kayla would have needed to pay for and send three score reports to each college. Now, she has the ability to send a superscore and all of its components in a single report. Students can opt to send colleges either a Superscore report or a test date report. Reports can be ordered from the Home page or the Scores page of a student’s My ACT portal. The ordering paths, though, have some unique advantages and disadvantages.

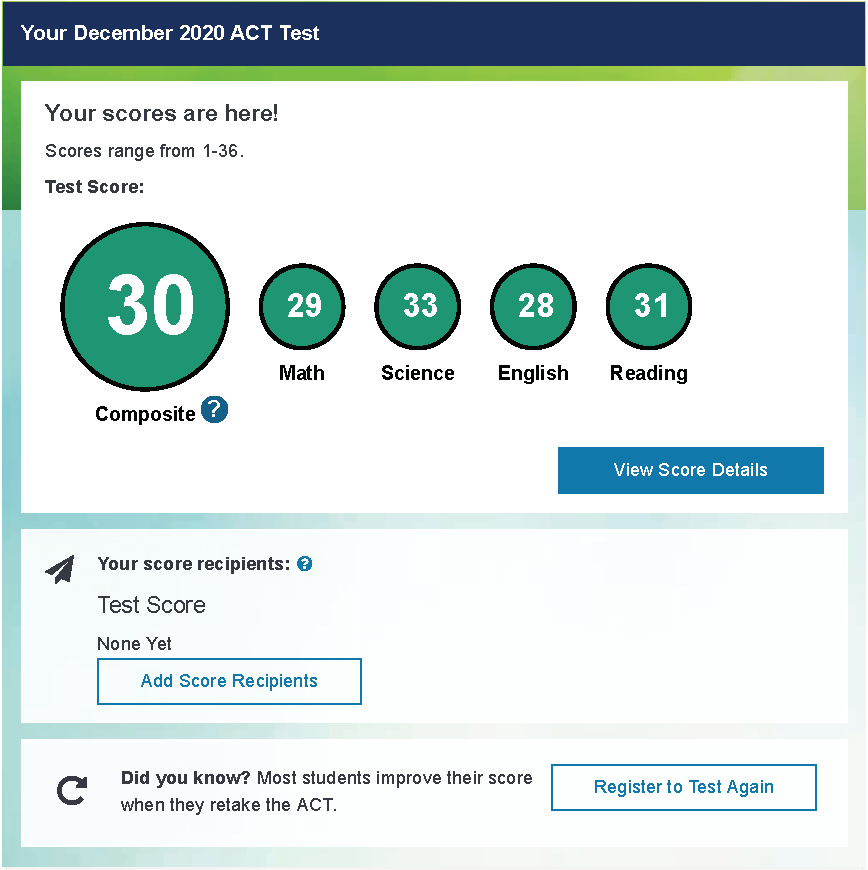

ACT now makes a student’s superscore the default view when logging into my.act.org.

Kayla’s most recent test date is listed, but it’s the superscore that gets top billing. ACT conveniently identifies the subject scores and test dates that comprise Kayla’s superscored Composite. Kayla did well in February, but she would clearly like to be assessed based on her superscore.

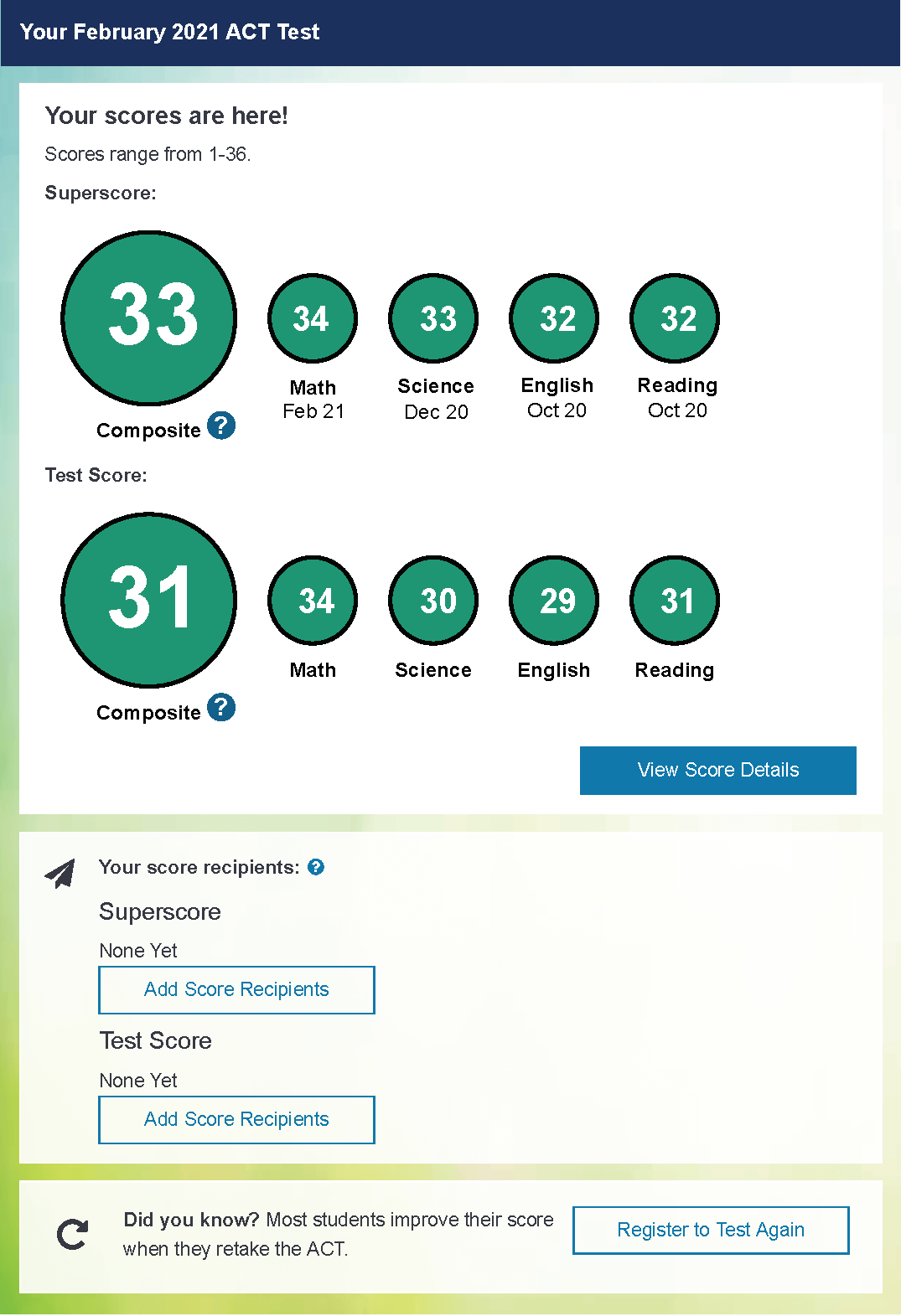

Kayla has two options to Add Score Recipients — one under Superscore and one under Test Score. The latter sends only her February scores. Both reports cost $15 per school as of April 2021. ACT typically increases prices with a new school year.

If Kayla scrolls to her earlier test dates on the Home page, she will not see the option to send a Superscore report.

She needs to go back to the top of the page to do that.

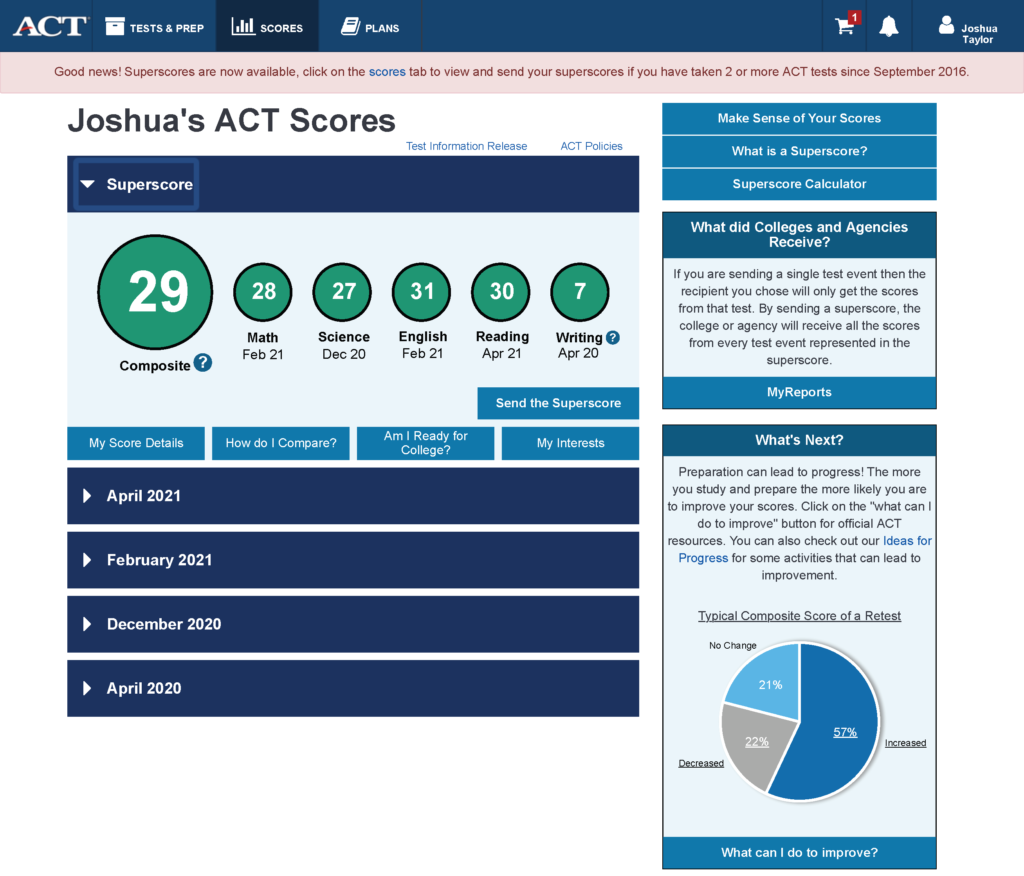

When students choose to View Score Details, they are taken to their Scores page.

Most students will find this a better jumping off point for ordering scores. Joshua, for example, can simply click “Send the Superscore.” Alternatively, he could expand one of the test dates and click “Send this Score” to send the results from that one sitting. Most students will go with the Superscore report.

ACT left a hole that needs to be corrected on the Home page. “Add Score Recipients” takes students directly to the college chooser without showing what scores will be delivered to colleges. When ordering from the Scores page, on the other hand, students are first routed to a summary view of the scores being sent. Students who miss this page may be surprised that colleges receive far more than just a superscore. If Joshua orders from the Scores page, he sees “What is Sent With Your Superscore?”

There are a number of idiosyncrasies. Where did that Writing test come from? Joshua took the ACT as part of statewide testing in spring of his sophomore year, well before he had done any studying. The state required that students take the Writing test. On his subsequent tests, he did not write the essay, since colleges have now dropped that requirement. [As of April 2021, West Point is the only significant holdout.] Even though his superscored Composite comes from his most recent test dates, ACT will still include his Writing score. Joshua would probably like to suppress this sub-par performance, but that’s not an option. We expect that most colleges will ignore this score.

Test date scores that aren’t part of the superscore line or the highest composite are not reflected at all. If Joshua had taken the test two other times and done poorly, there would be no record of the scores on the Superscore report. That’s exactly as he would prefer.

The Scores page is not perfect. Unlike on the Home page, a student can only see one set of scores at a time. Expanding one score will contract the others.

This means it is easier to spot trends from the Home page. The Home page also has the record of sent reports. The bottom line is that students need to learn their way around the My ACT portal.

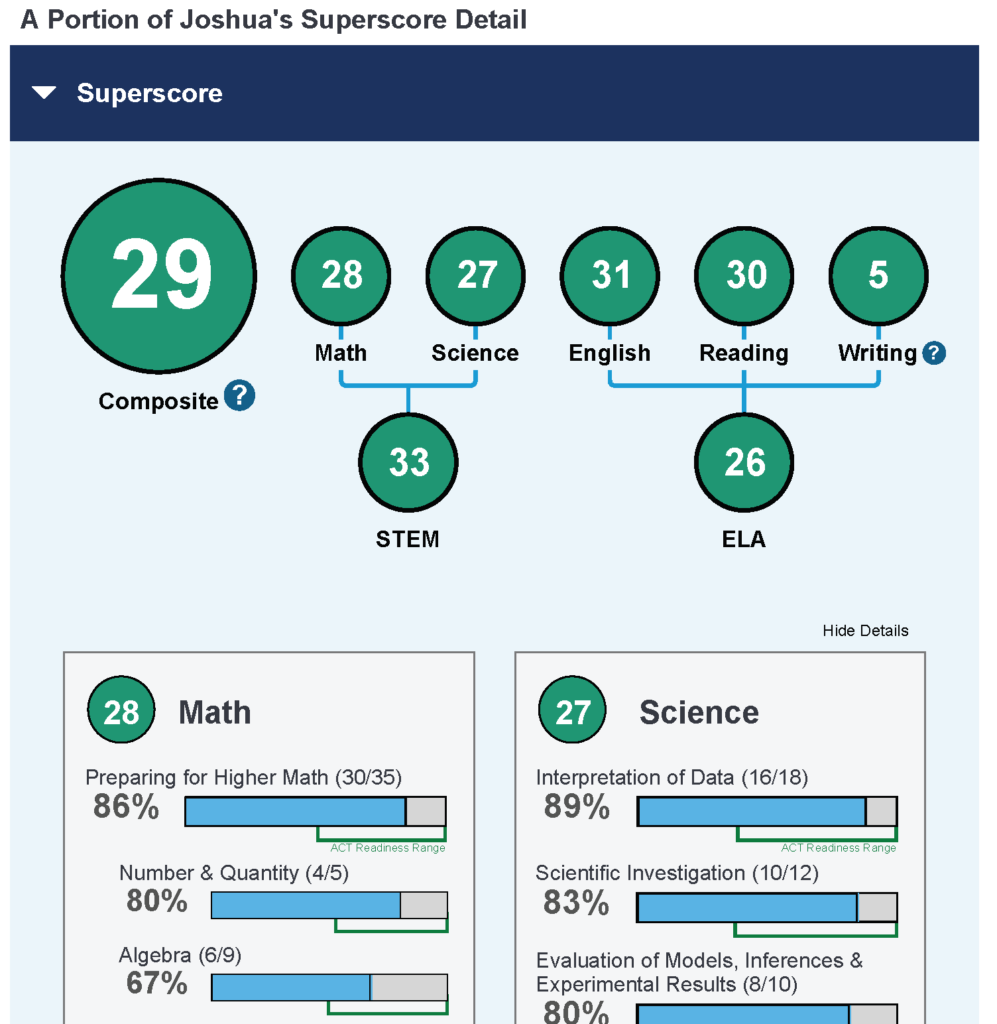

The Scores page is the place for Joshua to see additional detail about the superscore (or another test date). He gets subscore information when he clicks on “My Score Details.”

Percentile ranks are available by clicking “How do I Compare?”

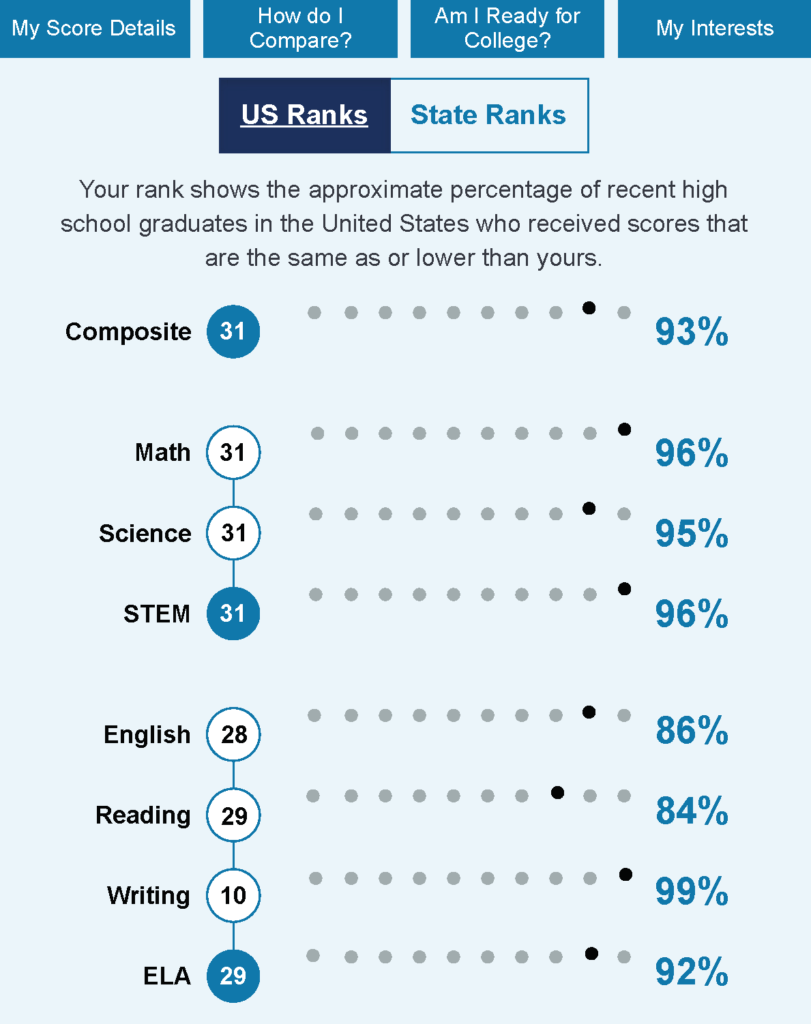

One of the first things students want to know about their test scores is how they stack up. Percentile ranks are meant to show exactly that. A percentile rank of 90 on the ACT, for example, means that 90% of students received the same score or lower. Flipped around, 10% of students had higher scores.

Superscores, however, create statistical inconsistencies in how testing norms are presented by ACT. The organization uses its traditional percentile ranks even though superscores are non-traditional scores.

ACT determines percentile rank using the most recent scores from the last three graduating classes. Because the ranks do not account for superscores, they underestimate the number of high scores. In the class of 2020, approximately 128,000 students earned a Composite score of 31 or higher based on the “most recent test” definition. Almost 158,000 students earned a superscore of 31 or higher. That means that such scores are 23% more common in the applicant pool when superscores are in the equation. ACT — at least based on the reports we have seen to date — passes along the same misleading norming information to colleges. Fortunately, colleges can easily see the actual distribution of scores at their own institutions.

Compass recommends that students compare their scores against the pool of applicants and admitted or enrolled students from target colleges rather than depend on national percentile ranks — especially when evaluating superscores.

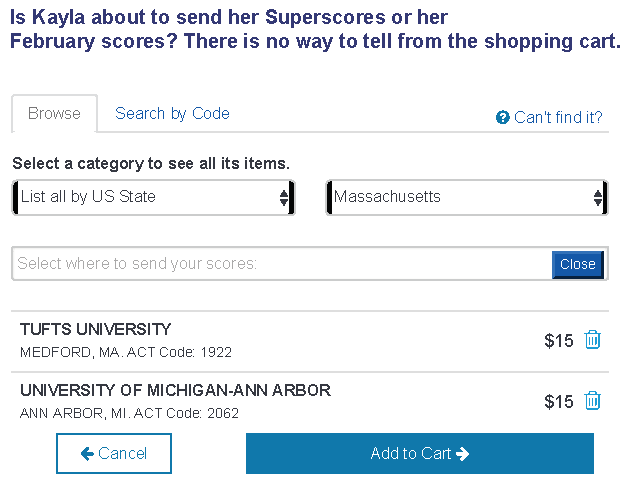

Depending on a student’s score mix, there are situations where sending Superscore reports is preferable at some colleges and sending test date reports is preferable at others. ACT’s interface makes it difficult to keep track of reporting during a session. A Superscore report and an individual Test Date report cost the same $15. What’s worse, ACT doesn’t label the type of report in the shopping cart. Students need to remember what they’ve chosen.

There is no option to mix-and-match report types or dates. If Kayla wants to send some colleges Superscore reports and some colleges test date reports, she will need to check out twice. Depending on the path she takes, in fact, her shopping cart may be overwritten without her realizing it. Students should send reports methodically.

In discussing the Superscore report with colleges, ACT discovered that not all schools were ready to simply ignore test date scores. To its credit, ACT built in fail-safes to ensure that colleges always receive a valid set of scores (this was even more important when Section Retesting was part of the plan). We saw, above, how Joshua’s report included 3 of his 4 test dates. ACT summarizes “ What did Colleges and Agencies Receive?”

A more detailed itemization of what scores are included in a Superscore report:

A student thinking she is just sending her superscores could be submitting the full set of results from as many as 5 different test dates, as well.

College Board’s SAT Score Choice model is more granular and has a superior interface. Students have full control over which dates to include, don’t have to worry about how College Board defines a superscore (it doesn’t), and can easily change their decisions college by college. We hope that ACT’s interface improves over time.

A Composite score is simply the rounded average of the 4 subject scores. This means that a 32 could be anything from a 31.5 (a “low” 32) to a 32.25 (a “high” 32). ACT has not stated whether it makes this distinction when using the tie-breaker on the Superscore report. In the example here, the student’s best performance was in December, but the superscoring tie-breaker rules imply that October and February would be sent instead.

We hope to clarify the distinction with ACT. The best solution would be to use a student’s highest summed score (M + S + E + R) rather than the simple Composite.

What about the 4 free reports that a student can order with each test registration? Those are not Superscore reports and apply only to the test date for which the student is registering. For students who want maximum control over their scores, the free reports are wasted.

Superscore reports are not updated after they are sent. If Kayla sends University of Michigan her scores in July, she will want to send a new report if she improves her scores in September.

The best alternative to the Superscore report may be not sending an official report at all. At an increasing number of colleges, students only need to send a report once an admission offer is made. Scores are simply self-reported on the application. Score reporting fees can quickly add up, and self-reporting is a simple way to ensure that colleges receive the scores you expect them to receive.

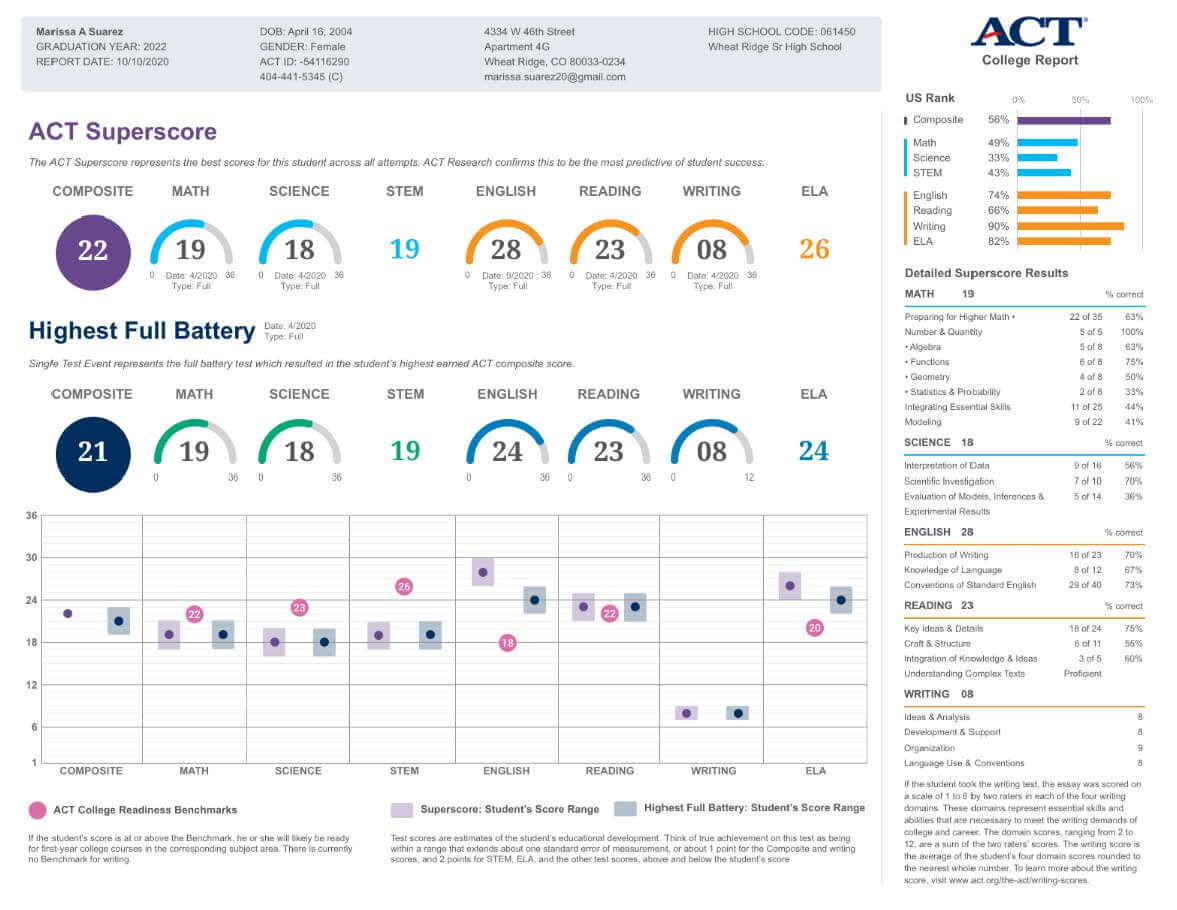

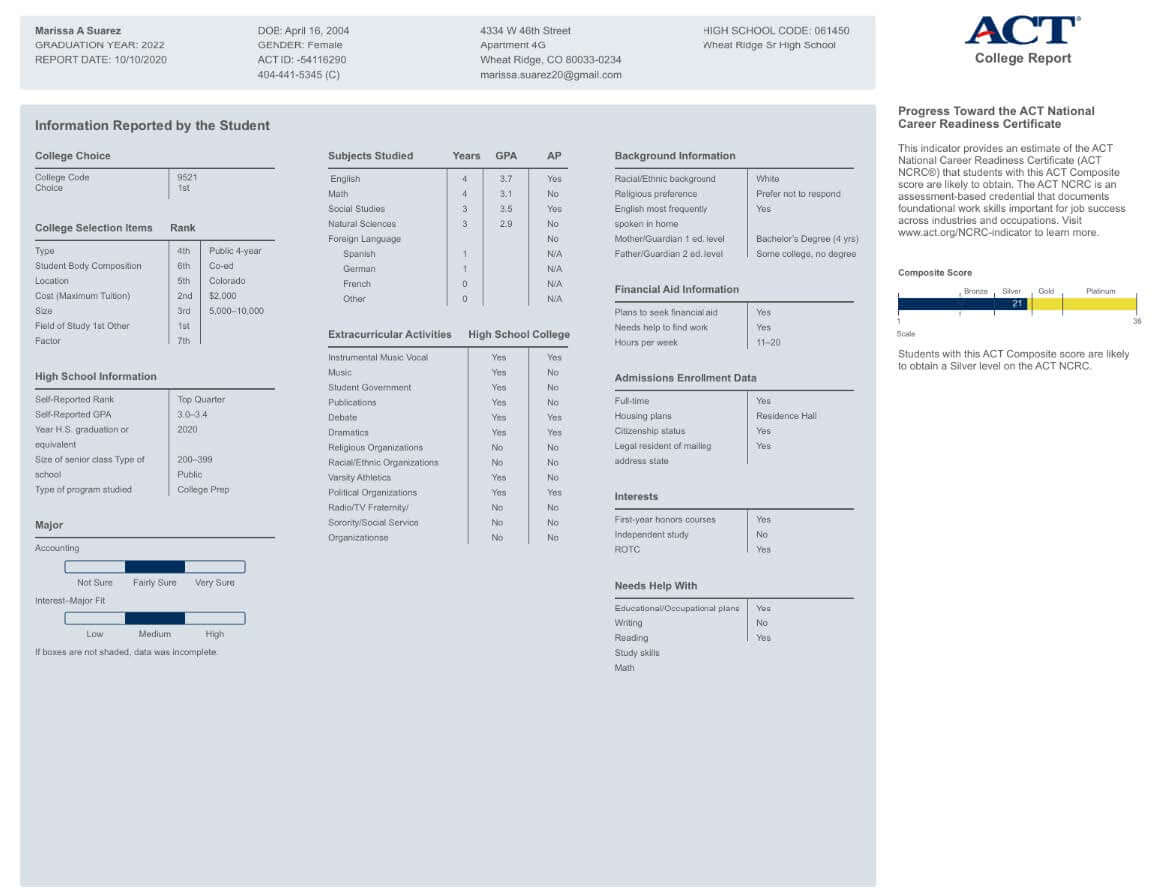

ACT’s and College Board’s reports have grown more complex and visual over time, so it is easy to forget that colleges are usually just downloading data files. Below are thumbnails for the graphical report sent to colleges.

The pages don’t reflect all of the information that schools can access. For that, the underlying data specifications are needed. They show the various scores provided to colleges and the large amount of information that students don’t always know is being passed along (e.g. ranked preferences of colleges, preferred types of institutions, and self-reported personal data about the applicant). There are 382 fields that colleges receive from each score report. Compass’s 2017 post on the College Report refers to the pre-Superscore version, but its insights are still relevant.

The larger problem is not in determining what scores will be received — that is knowable — but in determining how scores will actually be used. College Board made an effort (albeit one that is now outdated) to track which colleges allow Score Choice. ACT is not attempting to determine colleges’ policies on superscoring.

ACT answers “What will schools use?” as follows:

The second statement is meant to be reassuring. Unfortunately, it’s not universally true. Nothing prevents an admission office from evaluating all scores and subscores, and some explicitly state that they will. Colleges such as Georgetown, in fact, require students to send their entire testing records. Ultimately, applicants must take responsibility for ensuring that colleges receive the scores required and the scores that are best for the student. Superscore reporting is an improvement from ACT’s old system of score reporting, but it is not without its limitations.

Many testing policies have been frozen in place during the pandemic. With almost all colleges going temporarily Test Optional, little attention has been given to distinctions such as superscoring. As colleges update policies for the classes of 2022 and 2023, we will likely see an uptick in superscoring adoption. While Compass’s Superscoring Policies page is an excellent starting point, we recommend that students follow up with individual college websites for the latest information.

Even colleges that superscore may have different ways of treating scores. Some colleges will look at a superscore but will also review a student’s other scores. In contrast, schools such as University of Virginia — a standout in its transparency — don’t even pass along additional scores to admission officers. The computer system strips them out. That is the spirit of superscoring.

Section Retesting and Superscore reporting were meant to be a dynamic duo. As ACT watched the remodeled SAT retake the lead in admission testing, the organization looked for ways to make its own test more appealing. When students compared exams, the ACT had two distinct disadvantages. First, fewer colleges superscored ACT scores than did SAT scores. This wound was largely self-inflicted. ACT had long argued against superscoring. Second, students repeating the ACT faced the unenviable task of repeating all 4 subjects (and Writing, in the days when the essay mattered).

Section Retesting was going to be a secret weapon. It would allow students to choose which subjects to repeat. It would push the adoption of computer-based testing. It would encourage colleges to superscore the ACT. It would lead to more students opting for and repeating the ACT. COVID-19 imposed public health and budget constraints that made Section Retesting unworkable in 2020. For now, students have only half of the duo. Compass believes that they’ve received the better half. Even if Section Retesting does get rolled out in 2021-2022, full retesting will produce superior results for most students. A little extra time in the testing room can lead to a higher Composite and a higher superscore.

The classes of 2022 and 2023 cannot put their testing plans on autopilot. Test Optional policies are temporary at some schools and permanent at others. The University of California has gone Test Free — at least for the next several years — and may be joined by other colleges. The Subject Tests have gone away, so strong testers are looking for other ways of displaying their skills. Section Retesting might actually happen, and ACT keeps wavering about Remote Proctored exams (i.e. at-home testing). Superscoring is only one piece of the puzzle. Compass will continue to bring students and families the most comprehensive information as admission testing evolves.

Art graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University, where he was the top-ranked liberal arts student in his class. Art pioneered the one-on-one approach to test prep in California in 1989 and co-founded Compass Education Group in 2004 in order to bring the best ideas and tutors into students' homes and computers. Although he has attained perfect scores on all flavors of the SAT and ACT, he is routinely beaten in backgammon.